This Tuesday, the Center for International Affairs hosted a panel discussion on North Africa and the Arab Spring. In the aftermath of the Arab Spring, people worldwide are left wondering just how successful these North African revolutions were in achieving their core goals of establishing democracy, toppling authoritarian regimes, and promoting regional growth and peace. The three esteemed panel members shed light on where North Africa started, how far it’s come since the revolutions, and what progress still needs to be made.

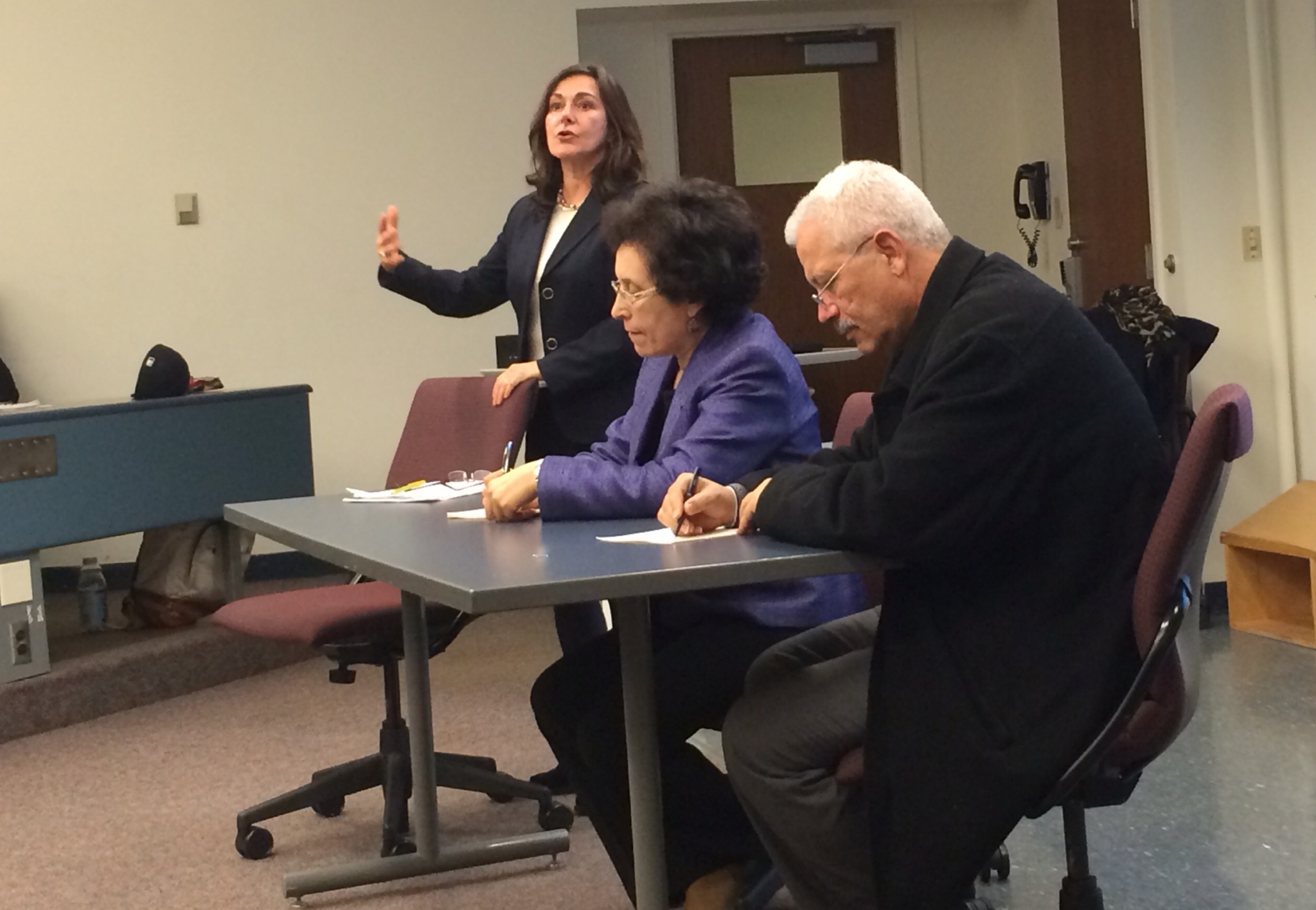

Students and faculty members alike crowded into a classroom, lining the walls and sitting on the floor when seating ran out. All were eager to gain some new insight on the causes and effects of the series of revolutions that took the world by surprise just over two years ago. Northeastern University’s very own Dr. Valentine Moghadam, director of the International Affairs and Middle East Studies programs and a professor of sociology, opened the panel discussion with a brief background of the Arab Spring and some of the women’s rights movements currently taking place in North Africa and the Middle East.

Dr. Moha Ennaji presented his thoughts next, mainly focusing on the change that has resulted from the Arab Spring. Dr. Ennaji is the president of the South North Center for Intercultural Dialogue and Migration Studies, co-founder of the International Institute for Languages and Cultures, and senior professor of linguistics and cultural studies at Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah University in Morocco.

Dr. Ennaji immediately grabbed the crowd’s attention when he succinctly summarized the Arab Spring in four words: “A search for dignity.” He went on to describe the rebel movements as being led by groups comprised of doctors, lawyers, and teachers, some secular and some faithful. These revolutions were not led by Islamists or al Qaeda, but by regular people who were sick of being oppressed and neglected by their governments. These were people who wanted change. After rebels successfully toppled the Bin Ali regime in Tunisia, the country went on to develop a new constitution championing gender equality, freedom of speech and religion, a separation of powers, and a respect for diversity.

To the untrained eye, Tunisia may appear to be the poster child for the massive success of the Arab Spring. However, Dr. Ennaji warned, “The implementation [of the constitution] is the problem in the region. We have some of the most beautiful texts in the world, but there is corruption on the ground.” It is difficult to say whether the new constitution in Tunisia and its neighboring nations will be upheld and obeyed, but Dr. Ennaji did provide some reasons to be optimistic about North Africa’s future. One of the most noticeable changes in the region is the recent shift in rhetoric: the ideas being preached in the region have become more realistic, and there is much more room for compromise now than there was two years ago. Also seen in some countries in the region is an abandonment of the implementation of Sharia law, effectively signaling a separation of church and state. Acceptance of a civil state including rights for women and minorities has also increased greatly following the Arab Spring.

So, what has the Arab Spring taught the people of North Africa? Dr. Ennaji believes that there is now an understanding that the marriage of Islam and politics benefits nobody. Political Islam has suffered a serious blow as a result of the Arab Spring, and the collapse of several military and police regimes in the region has provided an opportunity for the birth of democracy. The people want change centered around universal values that everyone can agree on: justice, freedom, and dignity.

Dr. Ennaji closed his presentation with a few recommendations geared toward effecting the separation of Islam and politics. He posited that in order to achieve this separation, North Africa should focus on improving its judicial and education systems, eliminating corruption, promoting democracy, reducing levels of illiteracy and poverty, and winning rights for minorities and women.

Continuing on the subject of women’s rights was Dr. Fatima Sadiqi, the director of the ISIS Center for Women and Development, a co-founder of the International Institute for Languages and Cultures, and a senior professor of linguistics and gender studies at Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah University in Morocco. She opened her presentation with a thought-provoking metaphor, stating somberly that Islamic feminism is the unwanted child of Islamism. Dr. Sadiqi explained that all types of women, young and old, secular and veiled, have fought for gender equality in recent years. She then drew a parallel between the recent women’s rights movements in North Africa and the first paragraph of Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities: “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of light, it was the season of darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to Heaven, we were all going direct the other way.”

Feminists rallying for equality for women in North Africa during the Arab Spring were working for a noble cause, but they knew that their goal would not be an easy one to achieve. Unfortunately, it appears to be a regional trend that women have less of a voice in North African government now than they did before the Arab Spring. The number of women holding seats in the Egyptian Parliament pre-revolution was 12 percent, as opposed to the current 2 percent. Women are also frequently accused of attempting to destroy Sharia law and aligning themselves with Western ideals, but in reality, most women strove to fight a secular battle against patriarchy, and wanted to improve Sharia, not abolish it.

In response to these challenges, Dr. Sadiqi recommended a strategic shift for activists. Most important out of these recommendations is the assertion that North African officials must acknowledge that women’s rights are a prerequisite to democracy. She also advised activists to take legal action to effect change in the new constitutions that are being drafted. Her other suggestions included stressing that gender is the main engine in economic development, and avoiding blaming religion for inequality. The final piece of advice she gave is to use social media to foster grassroots movements and try to make headlines around the world. Dr. Sadiqi’s closing remark was delivered with resolution and certainty: “Democracy will happen with women, or it will not happen at all.”

What stood out most to me was a comment Dr. Ennaji made during the Q&A session that followed the presentation. He implored the North African people to take a page out of Nelson Mandela’s book. “Do not fight each other. Do not destroy your country. Be tolerant. Have reconciliation. Be patient,” he explained. These principles reinforce the importance of everyone in the region contributing to the tedious democratic process by cooperating and moving forward without looking back.

The overall tone of the panel discussion was optimistic, and I left with the notion that the most important element in democracy-building is time. North Africa has effectively been turned upside down and completely uprooted over the past two years, and it will take years to build new governments, policies, and norms. It would be unwise to call the Arab Spring in any of these North African nations a failure, because democracy is a process, not a simple task. For years, developed countries have progressed at a rapid pace while the rest of the world has stagnated and even regressed. People in the most repressed regions of the world are learning the importance of fighting for their rights. The Arab Spring is just the beginning. I expect big things from North Africa in the years to come, because if history has taught us anything, it’s that people are willing to fight to the death for their dignity, and will stop at nothing until they are gratified. The road to democracy will be a long and bumpy one for these countries, but my hope is that with enough patience and persistence on the part of the people, all citizens will eventually achieve equality, democracy, and dignity. These are universal principles that humans of all nationalities and religions desire and deserve.

Jaclyn Roache

Political Science and Journalism ‘18