In the politically polarized city that is present day Washington, D.C., compromises are hard to come by. The need for criminal justice reform, however, is something that maintains near universal acceptance. From John Oliver to Ted Cruz, people throughout the country have spoken publicly of the need to mend the broken criminal justice system. While a multitude of ideas have been proposed and debated, one commonality among calls for reform is the need to reduce existing mandatory minimum sentences. Introduced in the 1980s and 1990s era of the“tough-on-crime” mentality, mandatory minimum sentencing results in the (often unwarranted) extended incarceration of individuals, leading to prison overcrowding, in addition to affecting racial minorities especially harshly. In response to this need for reform, the United States Senate Judiciary Committee wrote and passed the Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act of 2015, a bill which solves some of the justice system’s problems. However, to understand its potential benefits and shortcomings, the issue must be better understood in the context of criminal justice legislation and the current state of the justice system. While the Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act is well intended and accomplishes many reforms, the bill is merely a stepping stone to broader reform.

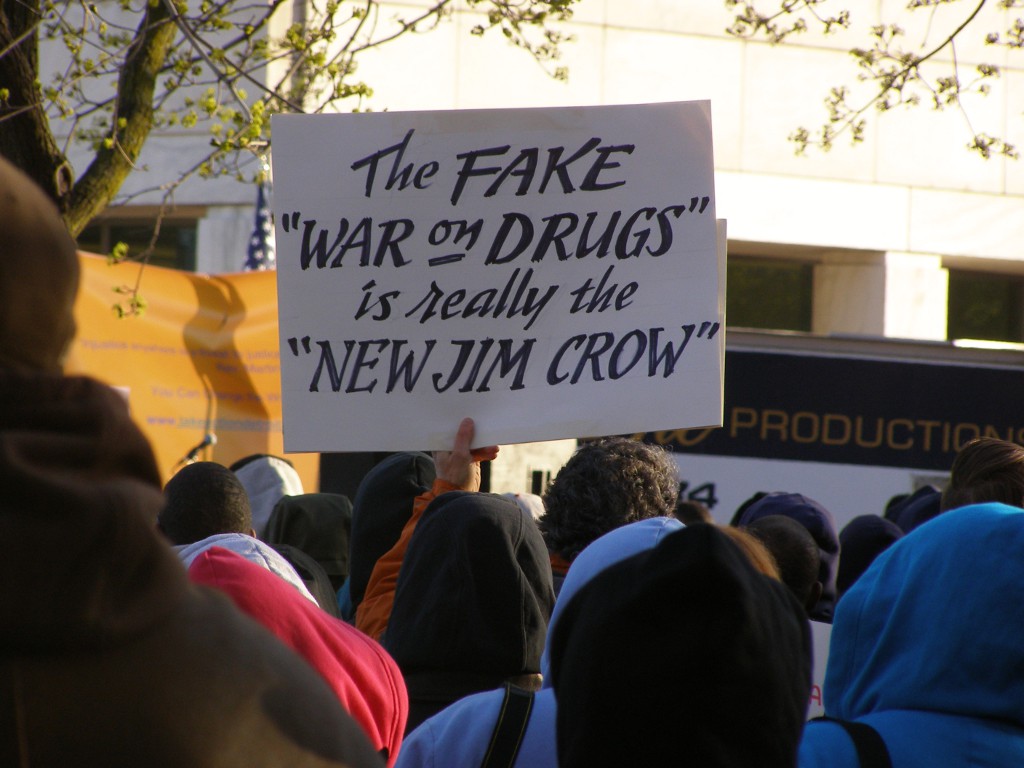

In the 1980s and 1990s, the nation was locked into the War on Drugs. Declared by President Nixon and furthered by President Reagan, a new wave of “tough-on-crime” legislation was written and passed with bipartisan approval. The Anti-Drug Abuse Acts of 1986 and 1988 declared the policy goals of eliminating drug abuse and established harsh mandatory minimum sentencing guidelines for many drug-related offenses.[1][2] A few years later, the 1994 Violent Crime Control Act, though mainly geared toward preventing violent crime, established more mandatory minimum-eligible crimes and expanded the three strikes rule to a broader array of offenses.[3] The impact the new sentencing guidelines created was immense; more and more people began serving longer and longer sentences. As a result of these laws, the number of prisoners at the federal level grew from 35,555 in 1985 to 205,020 in 2014, over 5.5 times as many inmates.[4][5] The contrast is even more stark with drug offenders; the population ballooned from 9,491 in 1985 to 93,262 in 2015, a factor of nearly ten. Due to the minimum sentencing guidelines established by these two bills, 48% of federal inmates are in prison for drug offenses.[6] While some are appropriate, many have been handed a punishment far harsher and lengthier than their crime would otherwise warrant.

Directly because of tough-on-crime legislation, federal prison overcrowding has become an issue. In 2013, a Federal Bureau of Prisons report estimated that the system was housing inmates at 36% overcapacity.[7] This overcrowding jeopardizes the safety of correctional institutions both for inmates and correctional officers. Additionally, the large incarcerated population places a heavy burden on taxpayers. In the fiscal year 2014, the Bureau of Prisons estimated the cost of incarcerating a person at $30,619.85 every year, or $83.89 per day.[8] At the federal level, this results in an annual expense to taxpayers of over $8.5 billion to maintain our current detention programs.[9] A more troubling result, however, is the racial disparity in the prison population that these laws have created. The overwhelming majority of prisoners are either Hispanic or African American, accounting for 34% and 37.7% of the current prison population, respectively.[10]

The inception of mandatory minimum sentencing greatly increased the magnitude of these issues. While imposed to crack down on crime and serve as a deterrent to potential criminals, studies have shown that the degree of the sentence bears little impact on its ability to serve as a deterrent. Rather, certainty of punishment has the most impact.[11] In addition to incarcerating people for longer lengths of time, mandatory minimums may actually increase recidivism and impede reentry into society due to the length of the sentence. Mandatory minimums also play a role in the racial disparities that exist within the prison population. In the sentencing process, 54% of Caucasians are sentenced at or above the minimum, while this is true of 67.7% of African Americans and 57.1% of Hispanics. For some reason, Caucasians are unduly more likely to be sentenced below applicable minimum sentences than other races. This inequity exists in the sentencing of career offenders as well, as African Americans make up about 49% of people incarcerated under the three strikes law in California. However, the most egregious problem with mandatory minimums exists solely in the difference between crack and powdered cocaine.

Under the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986, the federal government set a 100:1 crack cocaine to powdered cocaine ratio for tiered sentences.[12] This ratio meant that for people who possessed crack cocaine, the minimum sentence of 5 years applied at only 5 grams, whereas people who possessed the drug in its powdered form could have up to 500 grams before the minimum applied. While the drugs are chemically the same, the users of each vary widely. Crack cocaine is often more prevalent in lower-income areas or major cities, while powdered cocaine is found more often in middle- to higher-income areas.[13] This is reflected in the racial makeup of those charged with possession of the drugs. In 2009, 79% of people sentenced for possession of crack cocaine were African American, while only 20% were Caucasian or Hispanic. However, Caucasian and Hispanic people made up a total of 70% of those sentenced for powdered cocaine, while only 28% were African American.[14] As a result, though the two drugs are pharmacologically the same, African Americans overall were penalized at a much higher rate for a very similar offense.

In an attempt to remedy this inequity, in 2010 Congress passed the Fair Sentencing Act, increasing the quantity of crack cocaine that triggers the minimum sentence from five grams to twenty-eight grams. Effectively, this changed the sentencing ratio from 100:1 to 18:1, reducing the penalty many people would face.[15] While an admirable first step, the Fair Sentencing Act contains two main flaws. Despite reducing the ratio by a factor of over five, the principle inequity remains, as people are given harsher sentences mainly depending upon their socioeconomic class, the best determinant of the form of the drug consumed. The 18:1 ratio is therefore outdated, and only present as a compromise so that politicians can still present themselves as “tough on crime.” Second, while the legislation reduced the likelihood of unfair sentencing in the future, the Fair Sentencing Act is not retroactive. Therefore, while the Federal Sentencing Commission was able to amend the sentences of some, an estimated 5,800 crack cocaine offenders remain imprisoned under sentencing guidelines that are no longer law.[16]

To solve the inherent unfairness of the Fair Sentencing Act, the Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act of 2015 applies the Fair Sentencing Act retroactively, allowing some reprieve for inmates convicted of crack cocaine possession. Additionally, the law curbs the sentences required by the Career Offender provision of the 1984 Sentencing Reform Act.[17] Proposed changes include reducing the mandatory life sentence for a third drug offense to a minimum of 25 years imprisonment, and reducing the minimum penalty for the second offense from 20 years to 15. The proposed bill also provides a safety valve, allowing judicial discretion in some cases to prevent the overapplication of minimum sentencing. Under the proposed guidelines, judges would be allowed the ability to hand down below-minimum sentences to those convicted, provided that their crimes were of a less serious or violent nature.

In many ways, this piece of proposed legislation represents a great leap forward in combating the injustices of the current system. The bill takes into account many proposals offered by the Federal Sentencing Commission, which lauded several provisions of the bill. Specifically, the commission praised the expanded safety valve provisions of the bill for adding judicial discretion, allowing the judiciary to counter the racial disparities created by mandatory minimums. The report states that up to 3,314 offenders could benefit from the new provisions, providing savings to the taxpayer in the form of approximately 1,593 fewer inmates.[18]

In addition to the reforms provided by the Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act, a number of other proposals have been made to help further reduce both overcrowding and the racial disparity within prisons. While eliminating or reforming mandatory minimum sentencing to a greater extent would have a positive impact, ideas such as increasing access to both mental healthcare and alternative sentencing options such as drug courts both hold merit. Lack of adequate mental healthcare is a known problem in the United States, and studies have shown that race plays a role in ability to receive treatment. Specifically, Hispanics and African Americans are far less likely to access adequate care than their Caucasian counterparts, regardless of class or insurance coverage.[19] Increased access to alternative sentencing, such as drug courts, has also been shown to play a role in reducing crime and incarceration. A White House report stated that drug courts reduce crime in communities by 8-26%, while saving the taxpayer $2 in incarceration costs for every dollar invested.[20] However, while these are promising statistics, drug courts are underutilized, as 53% of United States counties are lacking this alternative to lengthy prison sentences. Additionally, even in counties with drug court access, minorities are still underrepresented as a portion of the participants 56% of the time.[21] Improving access to both mental healthcare and alternative sentencing would reduce both the enormous incarcerated population and the racial disparities within it, and would be logical next steps in combating these issues.

The proposed Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act of 2015 is a bill that would doubtlessly improve a situation where reform is needed. To remedy the injustices of the current criminal justice system, a balanced approach is necessary. The Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act of 2015 is a step toward this goal, through its changes to mandatory minimum sentencing and increased judicial discretion. However, this bill alone will not solve the nation’s criminal justice problems; rather, this bill should serve as a stepping stone to broader reforms in the future.

References:

[1] “Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986 (1986 – H.R. 5484).” GovTrack.us. January 17, 1986. Accessed November 22, 2015. https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/99/hr5484.

[2] “Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1988 (1988 – H.R. 5210).” GovTrack.us. 1988. Accessed November 17, 2015. https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/100/hr5210.

[3] “Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 (1994 – H.R. 3355).” GovTrack.us. 1994. Accessed November 22, 2015. https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/103/hr3355.

[4] “Trends in Corrections Fact Sheet.” Sentencingproject.org. November 1, 2015. Accessed November 14, 2015. http://sentencingproject.org/doc/publications/inc_Trends_in_Corrections_Fact_sheet.pdf.

[5] “BOP: Population Statistics.” BOP Statistics. October 24, 2015. Accessed November 22, 2015. https://www.bop.gov/about/statistics/population_statistics.jsp.

[6] “BOP Statistics: Offenses.” Federal Bureau of Prisons. October 24, 2015. Accessed November 14, 2015. https://www.bop.gov/about/statistics/statistics_inmate_offenses.jsp

[7] James, Nathan. The federal prison population buildup: Overview, policy changes, issues, and options. Vol. 42937. Congressional Research Service, 2013.

[8] “Annual Determination of Average Cost of Incarceration.” March 9, 2015. Accessed November 15, 2015. https://www.federalregister.gov/articles/2015/03/09/2015-05437/annual-determination-of-average-cost-of-incarceration.

[9] “FY 2015 Budget Request.” Justice.gov. 2015. Accessed November 15, 2015. http://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/jmd/legacy/2013/09/07/prisons-detention.pdf.

[10] “BOP Statistics: Inmate Race.” Federal Bureau of Prisons. October 24, 2015. Accessed November 14, 2015. https://www.bop.gov/about/statistics/statistics_inmate_race.jsp.

[11] Mauer, Marc. “Impact of Mandatory Minimum Penalties in Federal Sentencing, The.” Judicature 94 (2010): 6.

[12] “THE CRACK SENTENCING DISPARITY AND THE ROAD TO 1:1.” United States Sentencing Commission. 2009. Accessed November 15, 2015. http://www.ussc.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/training/annual-national-training-seminar/2009/016b_Road_to_1_to_1.pdf.

[13] Palamar, Joseph J., Shelby Davies, Danielle C. Ompad, Charles M. Cleland, and Michael Weitzman. “Powder cocaine and crack use in the United States: An examination of risk for arrest and socioeconomic disparities in use.” Drug and Alcohol Dependence 149 (2015): 108-116.

[14] Kurtzleben, Danielle. “Data Show Racial Disparity in Crack Sentencing.” US News. August 3, 2010. Accessed November 22, 2015. http://www.usnews.com/news/articles/2010/08/03/data-show-racial-disparity-in-crack-sentencing

[15] “Fair Sentencing Act of 2010 (2010 – S. 1789).” GovTrack.us. August 3, 2010. Accessed November 15, 2015. https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/111/s1789.

[16] “FAMM – » Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act of 2015 (S. 2123).” FAMM. Accessed November 16, 2015. http://famm.org/sentencing-reform-and-corrections-act-of-2015/.

[17] “THE SENTENCING REFORM AND CORRECTIONS ACT OF 2015.” United States Senate Judiciary Committee. October 1, 2015. Accessed November 13, 2015. http://www.judiciary.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/10-01-15 Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act Section by Section.pdf.

[18] Saris, Patti B. “Statement of Judge Patti B. Saris Chair, United States Sentencing Commission.” United States Sentencing Commission. October 19, 2015. Accessed November 17, 2015. http://www.ussc.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/news/congressional-testimony-and-reports/testimony/20151021_Saris_Testimony.pdf.

[19] Alegria, Margarita, Glorisa Canino, Ruth Ríos, Mildred Vera, José Calderón, Dana Rusch, and Alexander N. Ortega. “Mental health care for Latinos: Inequalities in use of specialty mental health services among Latinos, African Americans, and non-Latino Whites.” Psychiatric Services (2014).

[20] “Drug Courts Fact Sheet.” The White House. May 1, 2011. Accessed November 18, 2015. https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/ondcp/Fact_Sheets/drug_courts_fact_sheet_5-31-11.pdf.

[21] Huddleston III, C. West, and Douglas B. Marlowe. “A NATIONAL REPORT CARD ON DRUG COURTS AND OTHER PROBLEM-SOLVING COURT PROGRAMS IN THE UNITED STATES.” (2011).