This started out as an inside joke.

As I packed for my spring break trip to Israel, I asked my closest friends and family what they wanted as souvenirs. One said, “a cat that speaks Hebrew.”

When I reached my first tourist spot—an ancient grave—I spotted a stray. “Do you speak?” I joked as I took its picture. This should have been the end of it. So, why do I have twenty-two stray cats on my phone?

“If strays keep reproducing at their current rate, they will surpass the Israeli population within a few years.”

Israel has a massive cat problem; there are roughly two million strays in the country, with 240,000 in Jerusalem. The British brought felines to Palestine in the late twentieth century to combat a rat problem. But these cats repopulated wildly. Because of the warm climate, a female cat could have three litters a year (around nine to fifteen kittens). Additionally, food is plentiful in major cities, where cats eat from open dumpsters and trash littered throughout.

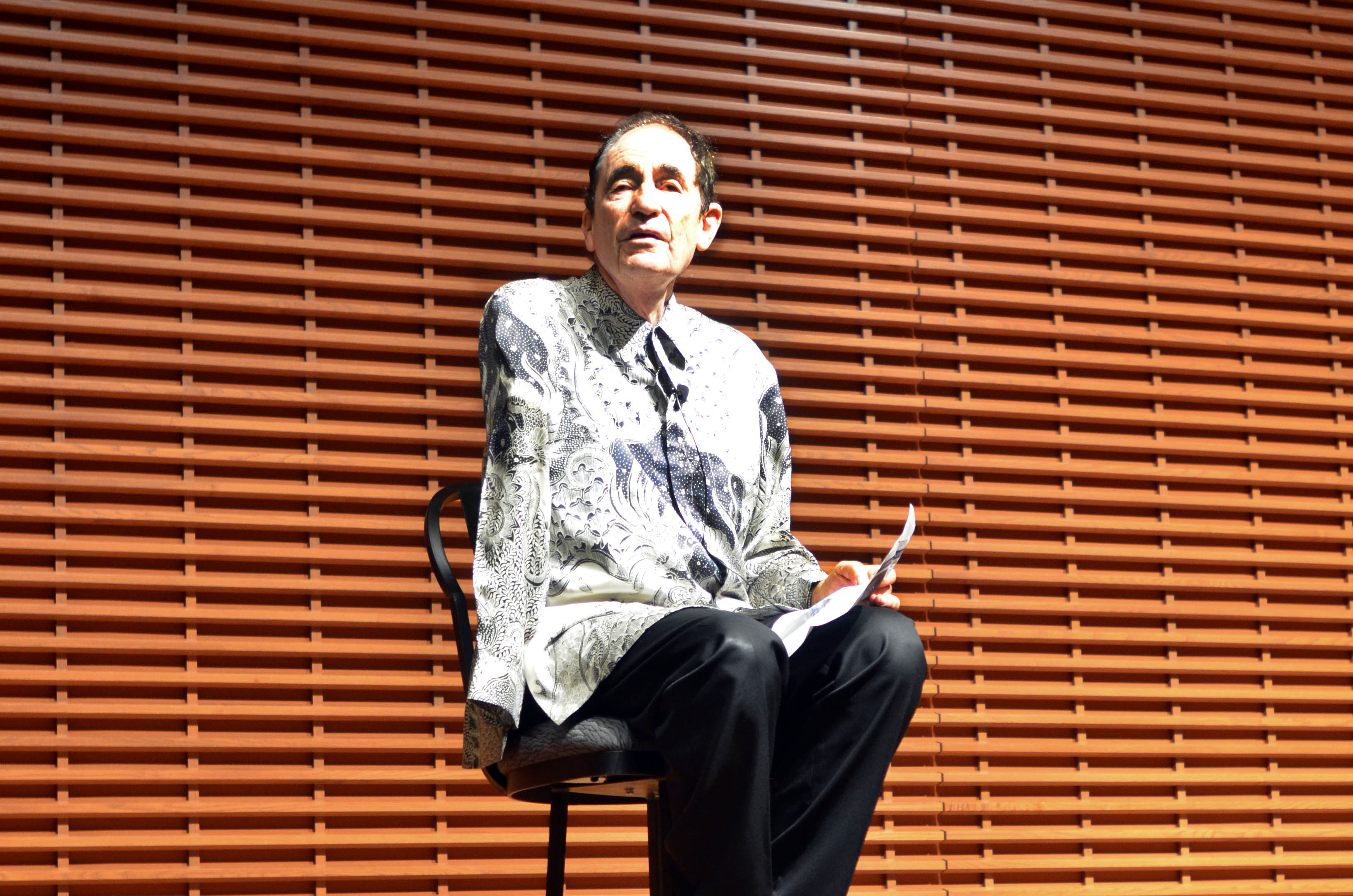

But when these felines can’t raid trash cans, they turn to hunting, which harms Israel’s ecosystem. These seemingly cute, cuddly cats are killing machines for smaller animals, including birds, snakes, lizards, and chameleons. If the cats eat enough to cripple their prey’s population, it creates imbalances further down the food chain. Furthermore, losing birds or reptiles means losing an effective predator for pests that destroy crops. Zoology professor Yoram Yom-Tov expressed that stray cats’ predation causes “lots of damage to wildlife.”

Strays are also host to numerous contagious diseases. One scratch on their bodies can turn into an abscess. For male strays, urinary tract infections cause severe blockages; their deaths are slow and painful. A cat with herpes, gone untreated, can go blind.

Strays also threaten the well-being of pet cats. Maintaining a cat in Israel is already expensive enough—pet shops, veterinarians, and the Society for Prevention of Cruelty to Animals estimate that basic routine care costs around 1,300 shekels ($387) per year. Costs can easily soar from add-ons like toys, high-grade sand, treats, injuries, and illnesses. Tack on unexpected veterinary bills for fight wounds or illness, and the expense is too much for many families.

Despite such negative impacts, Israel has not taken substantial action to quell the stray population. If strays keep reproducing at their current rate, they will surpass the Israeli population within a few years.

Israel would need to sterilize 80 percent of strays within six months to control the population. This is particularly difficult since the central government provides insufficient funding—4.6 million shekels (around $1.4 million) annually—to local governments for sterilizing. Underfunded localities end up doing nothing, skyrocketing the number of strays. To meet all the budgetary requests from local governments, the central government would need to double its funding.

Beyond financial obstacles, religious communities have pushed back on sterilization. In 2015, Agriculture Minister Uri Ariel expressed opposition to sterilizing programs for “running counter to the religious or ideological beliefs of various segments of Israel’s population.” He urged that the funds be shifted toward alternative solutions. In particular, he sent a formal letter to the environmental ministry advocating the deportation of either all the male or female cats. He allegedly cited “Jewish law against animal cruelty and a biblical commandment to populate the earth as reasons not to neuter cats.”

Needless to say, Israel had a laugh that day. The plan was not only infeasible—as Ariel failed to provide details—but also ridiculous. Right after he proposed deportation, #cat-transfer (in Hebrew) began trending on Twitter.

“We are going to war against cats in the name of God,” one Twitter user noted.

“Israel struggles to determine how religious it should be as a Jewish state. As a result, Israelis are divided on whether to follow Jewish law even when it comes to seemingly small issues like this.”

On the contrary, God is keeping these cats fertile.

Without a centralized plan, Israel will never tame its stray population. Zoology professor Shai Meiri believes euthanasia would be far more effective than sterilization. Yom-Tov echoed these sentiments, expressing that pets belong at home and not in nature.

Strays were regularly culled in Israel until 2004, when the state made killing them illegal, excluding cases where they threaten human life. While some have proposed starvation as an alternative—especially since cities are moving trash underground—this plan will force strays to hunt, further harming the ecosystem.

Adoption may sound like the obvious answer, but the associated costs serve as deterrence. Ellen Moshenberg, chair for Arad for Animals, notes that “cats are simply not held in high regard in Israel, where they are frequently likened to rodents.”

Clearly, no solution will completely rectify Israel’s cat problem and satisfy all concerned parties.

Trap, Neuter, Release (TNR)—the act of sterilizing, vaccinating, and releasing strays—is typically viewed as the most ethical solution. However, besides the religious opposition it faces, TNR does not address the ecological concerns zoologists and environmental conservationalists have. The results are gradual, leaving the environment at risk far longer than mass euthanasia. Culling programs face criticism from religious communities and animal rights activists who amount these programs to animal cruelty. Starvation, like TNR, would be slow and would endanger other species as the hungry cats turn to hunting.

Israel’s cat problem is tied to a graver, more pressing matter—secularism. Israel struggles to determine how religious it should be as a Jewish state. As a result, Israelis are divided on whether to follow Jewish law even when it comes to seemingly small issues like this. The result is a rising stray population that proves detrimental to Israel’s wildlife.

If Israel wants to control its stray population, it must take either a cat-first or wildlife-first approach. Whether it employs TNR, euthanasia, starvation, adoption, or a mix of these options, something has to be done.

Jews are the first people known to have adopted animal cruelty laws. Jewish rules on slaughtering animals for food were established to prevent unnecessary suffering. As Ariel expressed, Jewish law contains an entire code dedicated to preventing animal cruelty.

Additionally, God’s first commandment to humans (Genesis 1:28) gave them responsibility for populating the Earth and wielding “dominion” over other creatures. Jewish sages have interpreted “dominion” to mean responsible stewardship rather than unconditional control. In Islam, “animals have their own position in the creation hierarchy and humans are responsible for their well-being and food.” Christianity forbids animal cruelty and demands mercy toward creatures.

Adherents of each faith have a moral obligation to treat strays humanely. If sterilization and euthanasia aren’t humane, then how is letting strays die on the streets from painful diseases any better?

The religious communities that limit solutions must be at the forefront of this issue. Instead of proposing absurd policies like deportation, they should seriously consider TNR or euthanasia. While these solutions may not be perfect, they’re more ethical than doing nothing. As the species with “dominion” over the planet, we need to make tough choices. But that doesn’t mean that there aren’t other things that can be done. For one, Israelis could try to find ways to make adoption more feasible and attractive for families. Better yet, they could adopt strays themselves.

Despite my allergy, my family took in a cat that was at risk of homelessness because it was the ethical thing to do. My hometown of Philadelphia has around 400,000 strays—more than Jerusalem. But our city has a plan of action; in 2014, Philadelphia’s animal control team established the Community Cats program, which trains residents on how to best feed and shelter cats until they can be trapped. Once caught, these strays are sterilized and released. Beyond TNR, Philadelphia’s intake shelter looks for people willing to foster or adopt strays. Euthanasia is a last resort when cats are too sick to be released, fostered, or adopted.

It is too early to determine whether the policy has curbed Philadelphia’s stray population; however, it has helped prevent euthanasia—the save rate for strays improved from 63 percent in 2013 to 75 percent in 2015.

While cat lovers approve of these measures, environmentalists do not. Alley Cagnazzi, coordinator for the Community Cats program, notes that the environmentalists “care about birds,” while she cares about cats. There’s just no common ground.

We’re in the same boat; the only difference is that Philadelphia decided to prioritize cats over wildlife. It’s time Israel chooses too—otherwise, both will continue to suffer.